In this blog post, I’ll be discussing something that intimidates me, as a teacher and as an individual… poetry! Specifically, I’ll delve into my fear, and then force myself to face it anyways by diving into my favorite poem: “Wild Geese” by Mary Oliver.

In contemplating goals for 2021, I set myself a challenge: do scary-but-good-for-you things. The things that intimidate you, the things you want and should do, but you’re too afraid to do because it makes you vulnerable.

When considering my other goals: blogging, creating YouTube videos, and crafting podcast episodes… well, I figured out what I needed to do. Create a podcast series all about poetry.

Now, for some of you, this may not be terrifying, but for me, it’s scary as hell. Even though my first podcast series was all about The Odyssey, which is a poem (an epic), I don’t especially teach it as a poem. It is a story.

Even though I have a degree in English, even though I teach high school English, even though…. you get the idea.

Poetry is still intimidating!

I hardly read poetry growing up. If I did, it was in book style, like Out of the Dust by ….

(I LOVE this book! I wove into my ninth grade class when teaching Of Mice and Men! It was awesome.)

In high school? The requisite Shakespearan plays, which we really only watched the movies about.

It wasn’t until college when I was taught how to read the classic poems that I felt like I “got it.” Like I had a temporary ticket into the VIP section of the poetry club. After my bachelor’s, poetry again felt alien. Like a foreign language, when it wasn’t practiced and used everyday, it became “other.”

As a teacher, I don’t want my own worries to hinder my students’ learning or exposure, so I integrate it when it fits our themes. But still, I tend to ask them: “what do you think?” and then have organic (and, don’t get me wrong, amazing) conversations about the pieces. But, I still feel like an imposter. Who am I to teach them poetry?

Poetry is this impenetrable fog that only sophisticated and genius people get to enter, and I’m not one of those people. I don’t write poetry, although I would like to, again, see fear. But I’ve always felt, and I will admit that it’s an incorrect feeling, that in order to talk about poetry you have to write it, you have to memorize Shakespeare and know all the rhyming patterns and genres of poetry in existence. I know this is not true. I know this is not what I would tell my own students, but somehow I still have this insecurity.

Even with this baggage, I still love to read poetry, and I try to integrate poetry into my classes when they fit our themes. This year, I wanted to talk about a poem with one of my classes, and one student piped up and said,

“I hate poetry. It’s the worst. This is all that we read in my class last year and I hated it. I didn’t understand any of it.”

And I totally understood where the student was coming from. I didn’t like poetry until I was an adult, until I had a class that lit the way through the fog of poetry-dom for me.

All this is to say, I set the challenge for myself: study and talk about poetry in an approachable way on my podcast and blog!

I thought for this student, for my previous self, I wanted to talk about poetry in ways that would help everyone focus on the beauty of it, the meaning of it, the power of it, as opposed to getting caught up in the loft, intimidating, technical side of it. I want to show that you don’t have to be a genius or poetry wizard to enter the conversation.

Now, I’m not saying that I won’t do my research to make sure that I know what the heck I’m talking about. I will not intentionally skip over important aspects, to the best of my ability, remember, I’m just one person though, I’m human.

I will do my due diligence, and I’m going to make sure to focus on the areas that I think everyone would find valuable, the aspects and poems that are really interesting—I’m always open to suggestions and (kind) feedback! And I’ll admit there will be times when I don’t know certain things or when I’m leaving things out. Feel free to point out those things, nicely, to me. 🙂

Nonetheless, as I said, I’ve decided that this year I’m going to step up to the things that make me uncomfortable, so that way I can show my students that learning can be uncomfortable, but it’s worth the journey. If I’m asking it of them, I need to ask it of myself.

To kick this off…

I’ve dedicated my first episode in the poetry series to my favorite poem which perhaps makes this even scarier because I want to make sure I’m doing it justice. This poem is my favorite.

I can still remember the first time that I read it.

I was doing research for a class in my master’s program. We were working on a project to synthesize and demonstrate our beliefs about education and our own learning experiences. The goal with the poetry was to find a poem that encapsulated those beliefs and that would sustain us during the difficult times of teaching.

One of the recommended books our professor suggested we look at was called Teaching With Hear: Poetry that Speaks to the Courage to Teach by Sam M Intrator and Megan Scribner. This is a fabulous poetry collection even if you’re not a teacher but especially if you are.

In this book, I found the poem.

A poem that spoke to me on a fundamental level. A poem that I can look to for peace anytime I’m going through difficulty anytime I’m feeling overwhelmed.

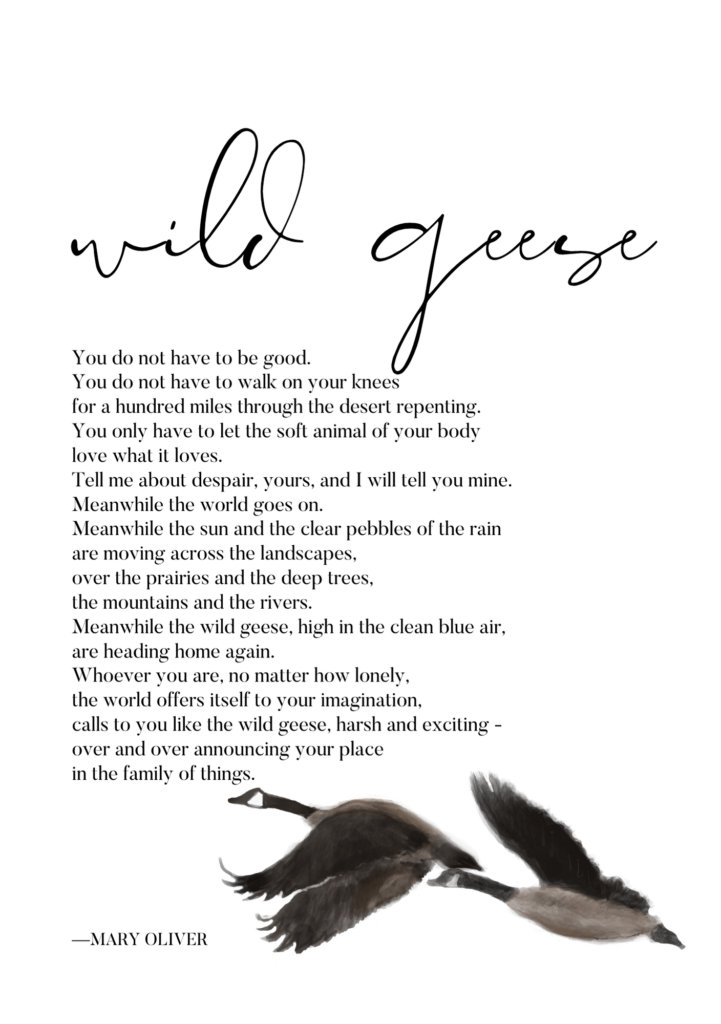

This poem is “Wild Geese” by Mary Oliver.

A Dive into Wild Geese

Before moving forward, please, please read the poem, or listen to Mary Oliver read it herself! If you’d like to see a lovely printable I’ve made of it, check it out here. It will surely add a little something special to your desk or wall! :).

Hopefully, you could feel the peace of this poem. To break this poem down, I’ll look at different aspects of the poem: messages, structure, poetic techniques, and favorite lines.

Messages

There are a few messages I’ve pulled from the piece.

There are overarching messages about the power of nature, the guilt of trying to be “good,” the power of nature, freedom and yet others. I’m going to talk about three meanings that are especially powerful.

One I find particularly compelling is the reminder of the temporary nature of difficulty. This poem reminds readers that no matter their struggles, life goes on. And not in a callous or unsympathetic way, but in a way that we all deal with grief or adversity, it is a part of life, and even though it feels like it, grief does not stop our life. We will eventually move forward. And, as a side note, perhaps that’s part of grief—our heartbreak that we will move forward and those we’ve lost will not.

Another message I’ve taken from this piece is the inherent sense of belonging. Even when it feels like we are disconnected and lost, when we feel misshaped and apart, we just need to take a step into nature to remember, we belong here.

Finally, a third meaning I’ve found comfort in is the idea that we can let go of perfection, of social constructs of “good” that trap us, we can release others’ unessential demands that confine us in the mundanity of life and just live.

I’m sure as you read this, there are yet other messages you can identify and hopefully find solace in.

This is what I love about poetry, there is never one layer, never one meaning. We can each read the same poem and find different pieces of what we need in it.

Structure

Next, let’s take a look at the structure.

This poem is written in free verse, which means it’s a poem that does not follow a prescribed structure, such as a sonnet or haiku. Instead, it flows and goes its own way. This choice is obviously not accidental or incidental, and it’s important to recognize this as a choice. Oliver is a master poet, and this use of free verse serves to bolster the messages of freedom and nature. Just as the speaker tells us we do not have to be “good,” this poem, too, does not have to follow the expectations and prescriptions of others.

Another structural aspect is the organization of the poem. It is all one stanza, it isn’t broken into different sections or “paragraphs.” But even though it is one piece, there is balance and organization within the stanza.

The first few lines begin with “you,” a direct addressal of the reader, then a line that makes a demand of the reader with “tell me,” followed by a few lines that all start with “meanwhile,” and ending with a segment that gives the reader a call to action, or rather an invitation or permission.

Poetic Techniques

The repetition mentioned earlier not only creates and influences the structure, but also lends to poetic techniques. Repetition, the poetic technique of reusing a word, tone, or phrase for effect, guides the reader through the poem.

“You do not have to,” repeats twice, followed by a closely related “You only have to,” These three phrases release the reader from their perceived obligations. It gives the reader the permission they shouldn’t need, yet do, to let go of that which does not serve them.

“Meanwhile,” which also repeats three times, reminds the reader of two ideas simultaneously. When I read this, I find the meanwhile comforting. No matter the struggle or grief I’m facing, the world is still moving. There is hope I can recover and join the world.

On the other hand, this meanwhile provides a sense of urgency. If we do not wake up and take advantage of this life, it will slip by us. We will miss the “harsh and exciting” call of life. Don’t forget, these lines say, that life will go on, whether you want it to or not, so take your place, live your life, love what you love.

Oliver also utilizes the poetic techniques of alliteration, anaphora, and enjambment.

Alliteration is the repetition of the beginning sounds of words in succession, or back-to-back. The most direct example of alliteration is “heading home.” I’ve read other analyses which list other examples of alliteration, but I don’t see many that meet the mark as closely as this. This “heading home” works because it comes toward the end of the poem when the speaker is reminding the audience that they geese are taking their place in the world, they belong, they are calling for you to do the same. These sounds, the comforting sound of home repeated, echoes the sense of belonging.

Anaphora is actually something we looked at earlier, the repetition of a “word of expression repeated at the beginning of sentences,” according to the dictionary. Again, the lines we discussed earlier, “You do not have to” and “Meanwhile the.”

The repetition here makes the poem feel like a conversation. It isn’t trying to lift itself above the reader, it is offering advice, a place to think and remember, to listen and be heard. This intimate feel is built in part by this anaphora. This is how we talk. We repeat ourselves. And this creates a comforting tone which allows readers to put their guard down and accept this advice, to feel at home within the poem.

Enjambment occurs when a poet runs a sentence over a line into the next — the sentence does not stop when the line stops, which forces the reader into the next line.

We see this enjambment in lines 2, 3, and 7. These lines do not have punctuation to sever the lines, and instead the reader must continue the thread into the next line. This works really well for the poem, because it echoes the message: “Meanwhile the world goes on…” Meanwhile this poem goes on, it does not pause when we always want it to, nor does life.

Favorite Lines

Alright, the glorious part of poetry! Looking at favorite lines. Well, I’m just going to be honest, every line is awesome, so we’re going to look at nearly everything.

Whew… I’m so excited and nervous! Let’s just do this.

“You do not have to be good.”

The word “good” here is the key. This word brings up an important denotative distinction. This is not talking about someone’s well-being, it is using the word at its intended meaning, it is looking at morality.

As a side note, I know it really bothers some people, and I’m going to be honest in my personal observations, that the “misuse” of the word “good” tends to be really scholarly people or older people. We throw this word around today a whole lot, and often “misuse” it.

“How are you doing?”

“I’m good.” or “I’m doing good.”

Technically, that’s not how we should use “good.” We should say, “I’m well.”

Good is a moral term. As such, this poem releases us from the pressures or moral goodness right off the bat.

This reminds us of the unrealistic expectations we have of ourselves or others to be perfect. Of never making a mistake. It also reminds us to be honest with ourselves, being “good,” moral righteousness, is a human and social construct. We choose to participate in these constructs, and I’m not saying we shouldn’t, but they aren’t natural. And oftentimes, they are condemning, they are heavy. And, again, oftentimes, they are hypocritical. Sometimes, we need to take a break from this judgment. From the weight of this moral judgment and perfection.

We carry guilt or fear or resentment around this “goodness” and our lack of it or our lapse in it.

But, the speaker reminds us, we do not have to be good.

“You do not have to walk on your knees

for a hundred miles through the desert repenting.”

Not only do we not need to “be good,” we also do not have to participate in the constant self-flagellation of “failing” to be good. We do not have to kneel in sand, or walk on our knees through the desert, asking for forgiveness, begging for repentance.

For me, this reeks of the biblical. I will admit I do not remember many Bible stories, so perhaps this is from a particular story or scripture. From my brief research, the desert does serve an important function in the Bible. I’m not going to go into that, I obviously don’t have enough expertise to talk about those stories.

Instead, I think the allusion to kneeling and repenting is enough for me to make the connection to religion, whether Christianity or another religion. Again, this follows up the moral-heaviness of the previous line, as religion is often a main vehicle for instilling morality into people and cultures.

However, this poem reminds us, we do not always have to beg forgiveness.

“You only have to let the soft animal of your body

love what it loves.”

I think this line is especially influential, and coming on the heels of the previous line, it digs deep in the reader. I know when I researched Mary Oliver after first finding this poem, I learned a bit about her personal life that could lend another way to read these lines. While there is intrigue and value in learning about a writer, it is essential to remember that work stands on its own. Unless it is deemed biographical or autobiographical, we cannot assume the piece is about the author’s own experiences.

Just like we don’t associate a novelist with the narrator, we likewise cannot associate the poet with their poem’s content. They are crafting a story.

This could speak to Mary Oliver’s own life, and how she may have decided to let go of society’s judgments on how she lived or who she loved. Or, it could be about anyone, and anything, that falls outside of the expectations others have.

If continuing with the religious hints form the previous line, this almost tells the reader they do not need to follow someone else’s morality at the expense of what they love.

Even if Oliver is not the speaker, this line still enforces the idea that you are only an animal, and although humans try to separate themselves from animals and nature, and we busy ourselves and shackle ourselves to traps of various kinds, we need not. We are “soft animals.” We need only love what we love. Do not deny yourself that love or feel like you must repent for it.

“Tell me about despair, yours, and I will tell you mine.”

This line, the wording, everything. I can’t even.

I just love it. This line is not offering a complaint session, this is a meeting of hearts and minds. A deep connection. Personal, individual connection.

To accomplish that level of intimacy in a poem is amazing. The speaker makes the reader feel seen and heard and valued. And they aren’t even face-to-face. The speaker is a figure of imagination! Oliver is magical. This poem is magical.

The intimacy of this line further connects the reader to the heart of this poem.

“Meanwhile the world goes on.

Meanwhile the sun and the clear pebbles of the rain

are moving across the landscapes,

over the prairies and the deep trees,

the mountains and the rivers.

Meanwhile the wild geese, high in the clean blue air,

are heading home again.”

While these lines could be discussed separately, they also function as a unit.

As with many of her poems, Oliver uses nature to ground the reader. While the speaker and their audience are sharing their despair, their hurts, the world goes on.

As I said earlier, this is comforting for a few reasons—no matter your suffering, life will continue. No matter your struggle, you will eventually come back to life.

“Whoever you are, no matter how lonely,

the world offers itself to your imagination,

calls to you like the wild geese, harsh and exciting –

over and over announcing your place

in the family of things.”

This segment brings all of the comfort home for the poem.

While earlier it seemed like the poet was in a small bubble with the audience, sharing their despair, now the poet speaks to everyone: no matter who you are, no matter your grief, the world is here for you.

The world is here for you.

How powerful to see it this way. How freeing.

The world offers itself to you, to your imagination. The world wants you here. It is inviting you out, to play, to create, to be.

And, the world is calling to you, don’t you hear it? It is calling and calling, just like the wild geese call. Over and over, the world tells you your place in the family of things.

This final line, “in the family of things,” tells everyone, you belong. You belong. You belong.

For me, this poem is a force. We all need a reminder that we belong in the world. We have a place in the family of nature, of the world itself outside of human constructions and trappings. This is why it’s my favorite poem.

We just need to listen to the call and heed it.

If you liked this blog post, or the podcast episode, please reach out and let me know! I’d love to hear what you think of the poem, and what poems you love.

Thanks for reading, or listening. Go answer the call of the wild geese.

References

Bolinger, Hope. “What Can We Learn from the Israelites Wandering the Desert for 40 Years?” Christianity, 16 Apr. 2020, https://www.christianity.com/wiki/bible/what-can-we-learn-from-the-israelites-wandering-the-desert-for-40-years.html

“Mary Oliver.” Poetry Foundation, https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poets/mary-oliver.

“Mary Oliver Reading Wild Geese.” YouTube, Uploaded by Stephen Roach Knight, 20 Sept. 2013, https://youtu.be/lv_4xmh_WtE.

Talking Leaves Podcast

Poetry Series

Episode 15: Poetry – Nourish Your Soul with “Wild Geese” by Mary Oliver

Recommended Book Club Reads

Recommended Book Club Reads 15 Professional (and Personal) Development Books for Teachers

15 Professional (and Personal) Development Books for Teachers The Ultimate Young Adult, Book Wish List

The Ultimate Young Adult, Book Wish List