In this blog post, I’ll review the exact strategies I use when teaching The Odyssey that help me and my students engage and learn from this epic tale.

Ahh, yes. The Odyssey. Perhaps the classic of all classics, still mandated in many schools across the nation. While I’ll refrain from waxing on too much about my thinking on this (I do touch on it a bit later in this post), I do believe there are texts perhaps more deserving and better fitting in the classroom than The Odyssey, all depending on the purpose of it. Keep reading to read more about that.

Nonetheless, you’re reading this post because you are, or will soon be, teaching The Odyssey. A monster of an epic. How in the heck do you get students invested in this piece? It’s ancient, it’s confusing, and… Odysseus is a bit… selfish. Well, his flaws and this story’s antiquity make it an intriguing task for us teachers. Over the past seven years, I’ve tried and failed at teaching this text, and below I will share with you what’s worked for me.

First, have a purpose. Why are you teaching The Odyssey? Think in terms of the summative assessment if that helps. Think in terms of the next unit, or the next semester. I discuss my reasons below, but the key: know why, and share them with students repeatedly throughout the reading.

Second, once you know your purpose, decide how much do you really need students to read, versus what they need to “understand.” The Odyssey is long, and even though you’re likely using a truncated version from the school textbook, it’s still long. What do students really need to read for comprehension? For analysis? And what parts can you read a bit quicker and follow up with a video summary.

Third, you have to get excited about something with teaching The Odyssey. I don’t like it too much, and I still find ways to get riled up to teach this. Namely, my distaste for Odysseus. Find something, hook into it, and share that with your students. If you are bored, they are extra bored. For me, this is sometimes bagging on Odysseus, or reading through a specific lens (feminist lens—why are the women nearly all villains? Why must Penelope be a saint?; contemporary lens—would Odysseus be a hero today? Do heroes today have fairy godmothers like Athena?).

With those ideas in mind, how do you actually teach The Odyssey?

Prepare Thine Students!

Book 1 of The Odyssey is con-fus-ing. Students never understand it, and the textbook version is a tadpole. It tells us nothing. So, before you even crack open the textbook, help students understand the Greeks and their culture and beliefs!

What do they need to know?

- Greek mythology & the activeness of the gods in Greek mortals’ lives

- Cultural concepts like Xenia and their desire to live grandly and be heroes (i.e. role of men = become famous or languish in the afterlife)

- Historical context of The Odyssey: the Apple of Discord, the Trojan War, and Odysseus and Penelope’s marriage

If you want further ideas on how to prepare students to read The Odyssey, see my post on pre-reading The Odyssey for different activities and free resources, and check out these activities from my TeachersPayTeachers store: Pre-Reading Culture & Context and The Odyssey Anticipation Guide.

Summarize Before Reading

This ties into your purpose. For me, the purpose of reading The Odyssey is a bit deeper than just comprehension. I want students to dive deep, to analyze it. To do that, comprehension and basic understanding of events needs to happen fairly easily. We can’t ask students to struggle to understand and then struggle to analyze. They will fatigue and fake-read.

So, help students understand the text before they even read it—give them summaries! Not only does this help all students, but this also helps your English learners and any students with different reading levels and abilities.

I’ve compiled a YouTube playlist with the summary videos I used with my own students, so feel free to check that out yourself.

Teach Students How to Annotate

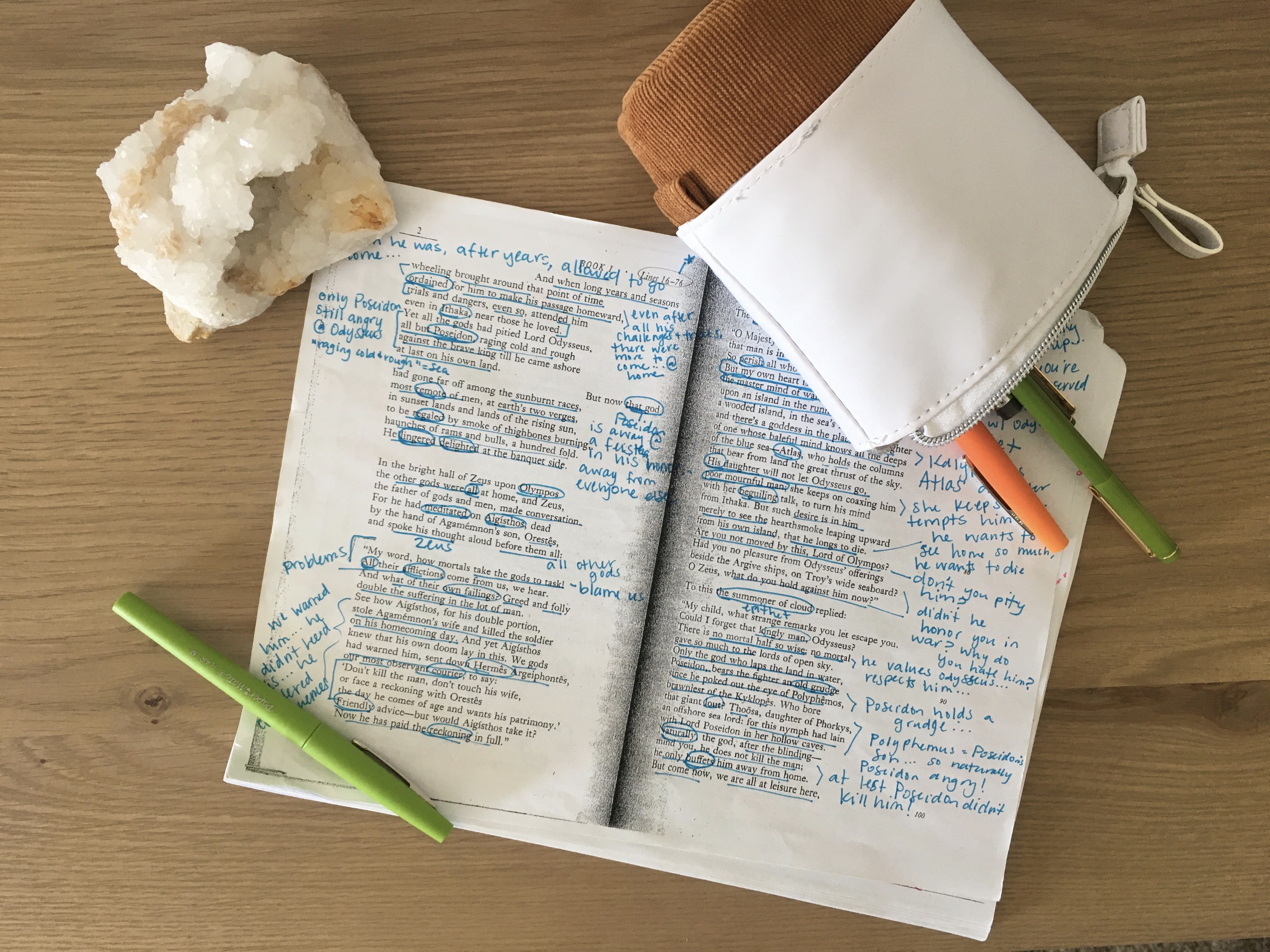

If at this point in the semester you haven’t really taught students how to annotate, this is your chance. Annotation is simply a fancy word for taking notes, specifically on a text, interacting with it on a deeper level than simple summary notes.

Some teachers use key symbols, like stars, exclamation points, question marks, and others as annotation. To me, that is not annotation. That is making symbols. Annotation is deeper—writing out your thinking. This can include symbols, but should also be more.

By writing out their thinking, students are (1) writing! (2) engaging with the text and story more fully, (3) preparing for future discussions, writing, and analysis right then and there. Instead of re-reading a whole book to remember what happened, they can just read their own notes! Time saver.

I model annotations live for my students and share my own notes with them (so, yes, each year I re-annotate The Odyssey with them… it keeps me engaged!)

For the first few books, we take notes together in class. Later on, you can have students lead the annotation and discussions using their own notes. See the next strategy for more on discussions.

I also show them videos about annotations, and I grade their annotations on a pretty basic level: done fully, mostly done, nearly done, incomplete.

Later on, I don’t have to grade every annotation assignment, but to begin with, the grade helps them see if they need to show more thinking in their notes.

This article from the University of North Carolina Chapel Hill is helpful in discussing the basics of annotations. In my eyes, the key to teaching annotation successfully means helping students identify their purpose for annotating. For example:

Academic Purpose: why are you reading?

- Scan for specific content (answer to specific question)

- Comprehension (overview; details & development of plot/characters)

- Analysis (specific lens; “deeper digging”)

- Literary Techniques/Functions

- Argument (to investigate author’s angle; to find evidence to build own argument)

- Discussion (focused? unfocused?)

- Writing

If you’ve also searched YouTube for a detailed, but not too detailed, easy to understand, short but not too short, goldilocks of a video on how to annotate, you know the struggle. There is too much out there, most of which seems intended for someone else’s classroom. I’ve made a, hopefully growing, YouTube playlist of the how to annotate videos I’ve found helpful. These videos, although not content specific, are helpful when teaching The Odyssey to prepare students for careful reading.

Daily Discussions

During the actual reading of The Odyssey, daily discussions should occur in some capacity. I tend to utilize small group discussions and check ins, followed by whole class discussions where the small groups share out. This past year, with distance learning and shorter class periods, I did a mix of small groups only, where I listened and checked in with all groups during a class period, whole class only, and a combination of small groups and whole class discussions.

Small group discussion are essential to make students feel confident and comfortable sharing with the whole class. Like me, you’ve probably started a discussion session and said, “ok, who wants to start us off?” And you’ve either gotten the most awkward silence ever, or you’ve had the one or two students talk the whole time, seriously, the whole time.

This is not good. You know this. So, prepare students by letting them hash our their misunderstandings in small groups! Tell them each group will share out, multiple times, and they each need to be prepared. Also, I like to give students a specific section to look at, or discuss, for 5-10 minute, and then transition to whole class, and after the whole class check in it’s back to small groups for the next section or question.

With the small groups, I made these heterogeneous, or mixed ability, so students could support each other in discussions. (For tasks or activities, I would have other small groups that were homogeneous or of the same ability—balance is important!).

Videos to Supplement and Engage

Make this reading come alive with videos. As I said above, summary videos are awesome. So too are analysis videos for teaching The Odyssey.

Like me, you probably use CrashCourse videos, they have an awesome one about The Odyssey, but it does contain spoilers, so decide when you want to show it.

You can also show certain sections of the movie version when teaching The Odyssey, we use the 1997 version (you can find usually it on YouTube), but… it does have some “suggestive scenes” like with Circe (the witch goddess who Odysseus has an affair with for a year) and Calypso (Odysseus’ seven year, maybe against his will, mistress). So, preview all clips yourself, and then show selected sections to your students. Mine love comparing and contrasting the movie versus the book.

Guided Reading – in a Podcast!

Purposefully Teaching The Odyssey

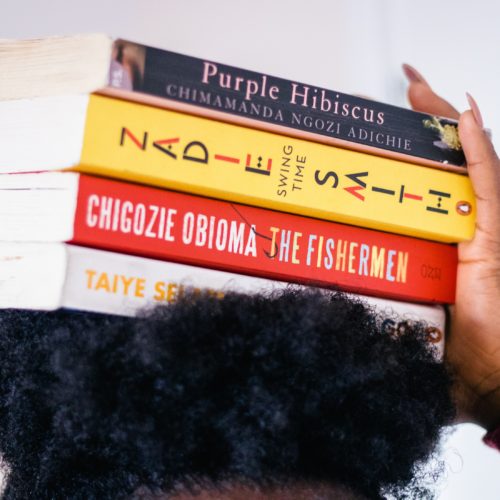

As we’ve said before, there is a perpetual struggle to interest and engage students in an archaic “classic.” Hopefully, your school, department, or whoever created the required reading list has a clear idea of why your students must read this text.

If you don’t have a clear idea… ask! Are there better texts for your students? Ones that will make them feel more connected, valued, and represented? Probably, so if there isn’t a clear “why,” then see if you can find an alternative.

So, why do I teach this text… well, to be honest, it’s a few reasons.

One, it is a classic, and one that colleges recommended students read. By the time my students graduate, they will ideally take English 1 at the community college, so we read this text to fulfill a college recommendation.

Second, reading this rigorous text and learning to annotate, discuss, and analyze it serves a key function in preparing them for college courses.

Third, thematically the hero’s journey and the epic hero archetype serve a central function for our English 9-10 course cycle. We analyze the cycle for a full year, and the other year we investigate other key archetypes: the tragic hero and the modern hero.

Fourth, my fellow teacher loves it. Me? Eh… I could take it or leave it. I do my best to be upfront with my students: Odysseus is not my boy. Honestly, I think he is a tool, and I challenge students to figure out how they feel about him. Further, I think my perspective allows students to see that they don’t always have to love something to find value and to engage with a text or idea. Sometimes it is in my own, and my students’ best interest to teach something outside my comfort zone, outside my interest, so they can see how to do that themselves.

Teaching The Odyssey with a Little Help

With all that said, you’re doing it, your teaching The Odyssey. Help your students even when you aren’t “with them” by providing them a resource made by a teacher (me!) for the classroom. This past year, I created a podcast mini-series to support my students when reading this text. Without face-to-face time, without seeing most faces at all (the Zoom black screen void), I needed a way to support them through the reading because I wasn’t getting as many cues on their understanding as usual.

Thus, the birth of the Talking Leaves podcast and The Odyssey mini-series. While I created this for the exigent circumstances of this school year, I definitely plan to keep using it. I feel like I shouldn’t toot my own horn, but my students loved it. In fact, one student, who is a bit of a reluctant engager, had so many questions about the podcast creation process and whether I was going to keep making them. It was an amazing conversation!

Perhaps you wont have the same conversations, unless you decide to make your own podcast, but the episodes’ content themselves is, if I do say so, supreme.

Comic Strip

Undoubtedly, you’ve seen this before, and perhaps even done this yourself — we don’t need to create fresh new strategies every time when teaching The Odyssey. Tried and true have their place! If you haven’t done this before, the concept is simple. Give students a piece of printer paper (or bigger paper if you have it), and they fold it into 6-8 squares. Each square = one book from The Odyssey. Students must illustrate a key event from that book in that square. This leads to more thinking about and comprehension of key events and even character development. This same strategy could be applied to over texts too!

I like the comic strip because it feeds the needs of the artists and visual thinkers in the classroom. It challenges students to think in a new way, and offers them opportunity to destress. Yes, you read that right. There is a correlation between drawing, even if done “poorly,” and lowering stress. Give yourself, and your students an opportunity.

Plus, you can ask more of your students than just a drawing. For mine, they must include a caption in every box, and they must choose a quote, two to three lines long, from that specific book.

Quick or Short Writes

More than likely, you will have students write an essay, or perform some sort of summative analysis project, upon finishing this epic. Ideally, with backward planning, you and your students know what this task is during the entire reading process. With that in mind, you can help students develop their thinking about this task, the main idea, along the way, with quick writes.

I love quick writes. Generally, students do these without complaint. You’ve set a timer for 5 or 10 minutes, and they just write. They don’t have to worry about grammar, or spelling, or any of that other stuff. They just dump out their thoughts.

Sometimes, all right, most of the time, students don’t see how the quick writes connect or help them… until the end. But, they still hardly complain about them. When they can look back at these to help them with their essay. So, just keep reminding students, “you’ve already thought about this, look at your quick writes.” During my first year of teaching, I used physical notebooks, and that made students diving back into them more seamless — they had to flip past them every day. Now, because everything is digital, students have to find the file and look through it… surprisingly difficult for them to do!

Quizizzs

I think I’m late to the Quizizz game. Previously, I used Quizlet Live! and Kahoot! as formative assessments and games. Quizizz is superior, especially for distance or hybrid learning. It generally lets students go at their own pace, and there are so many quizzes already there!

My students had so much fun! We did these live, synchronously together. And, we also took these asynchronous because you can schedule them through your learning management system, and also close the quizizz at a specific time. It’s awesome.

Throughout the week of reading a specific book, we would take practice quizzes for no points. At the end of the week, after discussing and dissecting the book, we’d take a graded quiz. I also offered retake opportunities. I made a few, but I also found a few.

Essay Writing

Yes, I am one of those teachers who tends to stick to an essay at the end of each unit. Do I have students do other projects? Of course! Again, my students need to write a lot to prepare for English 1, so we write at least three key essays a semester. Is that a lot? Not quantitatively, but we teach the full writing method:

- Comprehending the prompt

- Thesis

- Outline

- Rough Draft

- Feedback & Revision

- Final Draft

- Self Reflection & Self Grade

There are plenty of other projects you can have students do that utilize similar thinking skills as writing an essay, so don’t box yourself or your students in. If you want to do something else, I suggest utilizing the quick writes in a more formal way, where you assess students’ writing. Consider calling them “short writes” and requiring students to develop a clear thesis, use evidence, and generate explanation and analysis.

If you’re interest in seeing the prompts I use for The Odyssey, I’ll be sharing those soon and making them available on TeachersPayTeachers.

Essay Self-Reflection & Self-Evaluation

This has been a game changer for our English program. I have heard the argument that students will always give themselves a better grade than they deserve, they will just say “A” because they tried hard… I’m here to tell you, I hardly ever have that happen. We developed a system, based on this article, to train students to critically evaluate their own writing based on our rubric, and we show them what A writing looks like. We give them lots of feedback during the writing process, they know where they stand.

Maybe at the beginning of the year, with new students, I will have a few students who claim they earned all A’s according to the writing rubric, but that doesn’t remain the cause when we conference. Yep, a key component of this is to talk with students about their self evaluation. So, we also conference with them when possible (distance learning has made this challenging!), or we give detailed feedback on where we agree and disagree with their self assessment.

How do we do this?

Well, I plan to write a full post about this, and to give away some freebie guides in my monthly newsletter (sign up here!), so you can read the full details soon. In short, we analyze the rubric with students. We show them model writing and walk them through it.

We give feedback on key areas during the drafting process. And we provide focus questions that guide their self-analysis toward the areas we are really working on.

With exception of the final essay of the year, it’s good practice to focus on a few key aspects of writing, and emphasize those in teaching and in grading. This not only cuts down the time it takes to grade writing, but also makes it less overwhelming for students. They don’t have to , and can’t, be perfect writers–neither are we, their teachers! Instead, they must demonstrate competency in a few key aspects that we explicitly taught. Other areas should function, but perhaps aren’t stellar.

If you want to hear more about my philosophy of grading writing, let me know in the comments!

Want access to free guides, plans, and activities? Sign up for my monthly newsletter.

These are the strategies I use nearly every year to help my students understand and analyze The Odyssey. If you use other methods, I’d love to hear about them. If you try any of these out, also let me know.

I hope you feel inspired to try something new, or try something old in a new way. Happy teaching! 🙂

Song Battle Project: Teaching Songs with Rhetorical Analysis

Song Battle Project: Teaching Songs with Rhetorical Analysis The Ultimate Young Adult, Book Wish List

The Ultimate Young Adult, Book Wish List Backward Design: The Theory & In Practice

Backward Design: The Theory & In Practice