In this blog post, I share a unique project to engage students. Read on to learn about the song battle project and how to use songs with rhetorical analysis.

This year, I’m teaching a junior and senior English course, and I’m lucky enough to have extreme curricular freedom. In fact, I’m revamping a course that I created a few years ago: Poetry & Fiction. While this is many teachers’ dream, and even my dream, to teach a class they completely designed… I don’t always enjoy teaching these grade levels.

In the spring, juniors and seniors become more moody and less interested in the classroom. In general, I’ve found it helpful to combine grade levels; at a small school, it creates greater scheduling flexibility, and it also helps create a greater sense of maturity. However, with these combined classes, spring semester arrives, and it seems like senioritis takes over for the juniors too. This is especially frustrating when I feel so invested in the content, skills, and ideas because I belabored over crafting and organizing them.

In planning the spring semester, I did my best to consider the students in my classroom, their backgrounds and funds of knowledge, their interests and passions, and their histories and goals. I was feeling incredibly inspired after attending NCTE 2022 and after reading Gholdy Muhammad’s Cultivating Genius. With considering my students’ backgrounds and interests, I planned out the semester.

I would teach about rhetoric through relevant and engaging media; there would be opportunities for choice and investigation into their own interests. Although this all sounds exciting, I also was realistic. I have an interesting dynamic of students in my class–don’t we all?–and while some might buy into my hopes and plans, others would still be reluctant.

With this in mind, I knew I needed to protect pockets of time for joy and relevancy where, even with senioritis going strong, students would still want to come to class and engage. One caveat, though, it needed to tie into our goals and content–it should detract from these. After thinking about my students, I realized I could revamp a pre-existing project into something more game-like. They could use something they love with something they need: songs with rhetorical analysis. Hence, the birth of the Song Battle Project.

Song Battle Project: Overview

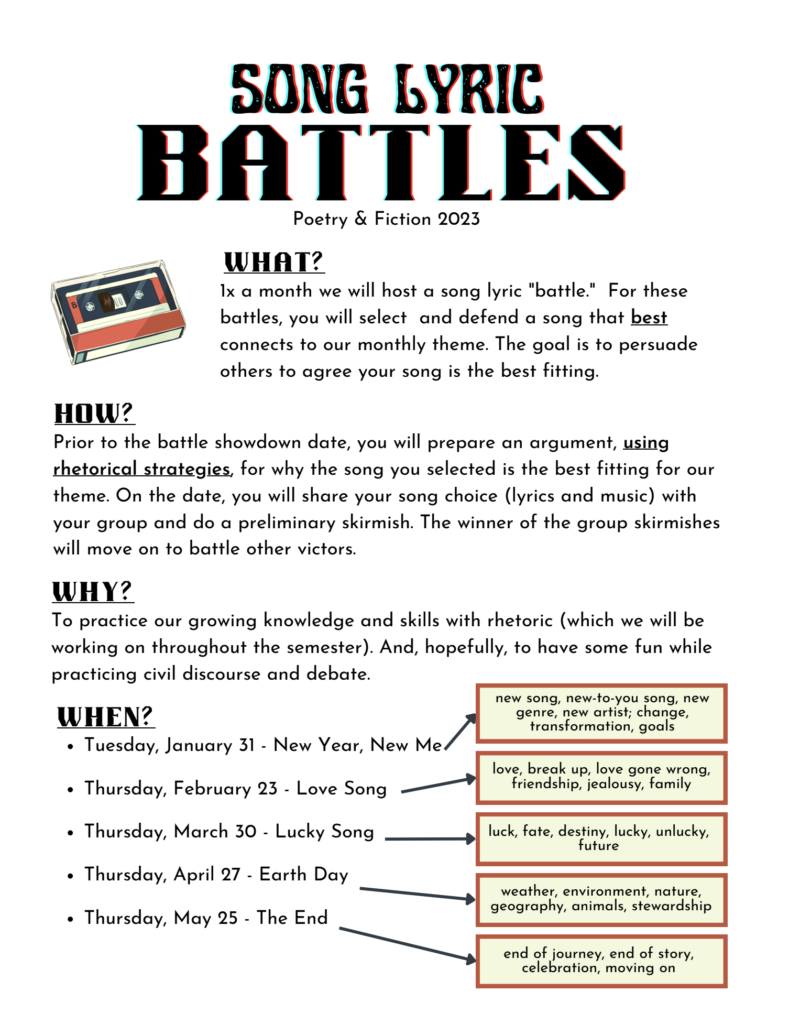

Ultimately, the Song Battle Project is a structured discussion in which: (1) students choose a song that fits a specified theme, (2) students prepare a rhetorical argument for why this song is the best fitting for the given theme, (3) students present their arguments, (4) students evaluate each other’s arguments, and (4) students vote on the “best” argument and the winners advance to further rounds of discussion/argument.

For my class, these battles happen once a month. In January, the theme was “new year, new me,” and my students and I discussed the possible subthemes of this topic. The song could be new to them; a new artist or new-to-them artist; a newly released song; a song about change or transformation; or a song about goals. In the end, this was their directive: find a song that you think fits the theme in any way, and craft and present an argument to prove your song choice is the best.

By the sound of talking and music playing throughout the room, they seemed very excited about this project. Some students already knew their song, others were creating playlists with possibilities and then choosing later. The room was buzzing.

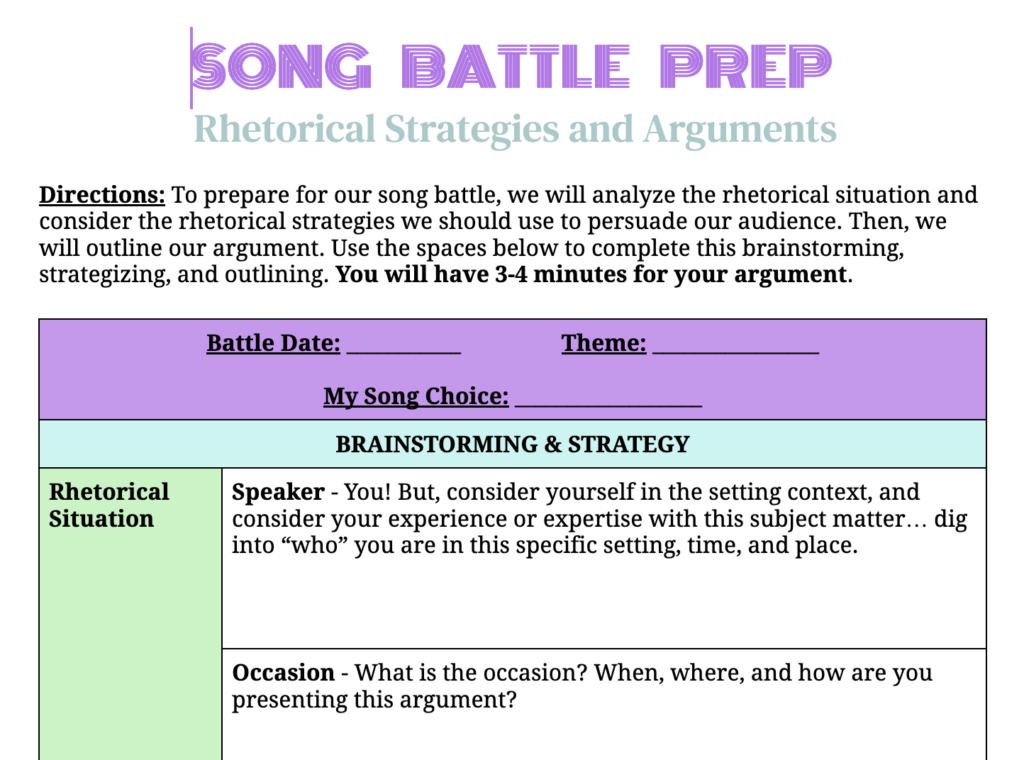

Fast forward to a week before the battle. I reviewed the planning document with students–the goal was not only to choose a song but to practice the rhetorical strategies and Aristotelian appeals (ethos, pathos, logos, kairos) we’d been studying. Of course, this went over less enthusiastically, but most of the class went to work brainstorming their strategies and then outlining their argument. The document asked them to consider their audience, purpose, and goals. In other words, students had the opportunity to integrate their love of music and songs with rhetorical analysis.

Song Battle Preparation

During these planning sessions throughout the week leading up to the battle, I answered questions. How do I use ethos in this type of argument? Who decides the winner? Is everyone going to have to listen to our song? How long do we have? What does the winner get?

These were my answers:

- Ethos can come from you if you feel especially passionate or knowledgeable about music, this song, this artist, or this topic. It can come from the artist themself; who are they? What are their accomplishments? Ethos can come from the song–is it popular or famous?

- In the first and second round of the battle, the group will vote on the “best argument,” and that person will move to the next round. Everyone who does not progress to the next round becomes an audience member and voters.

- During this battle, we would not have enough time to listen to everyone’s songs… think about the math of that! So, as part of your argument, consider if you need to play a small clip of the song, 15-30 seconds or so.

- Please read the directions. (Yes, I’m mean and make them read the directions rather than answer their questions.)

- The winner gets the joy of victory… isn’t that enough? (they booed at this and wanted candy.)

Modeling

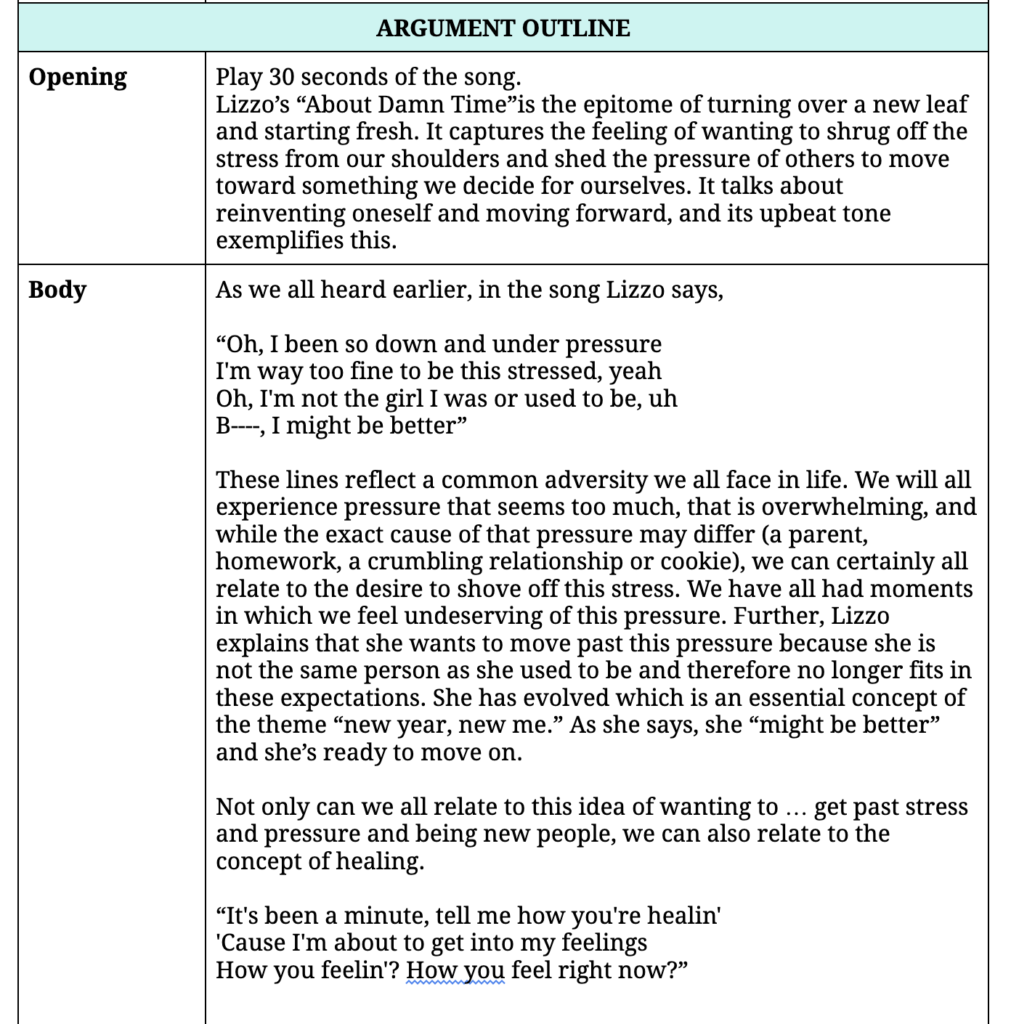

I also gave them a rough example of how they could brainstorm and present their argument.

I told them, for this theme, I would choose “About Damn Time” by Lizzo, which, to my surprise, somehow generate a collective “ahhh,” and “oh my god.” And not in a good way, as in a “of course you would” and “we’re disappointed way.” I expressed my shock and dismay–Lizzo is awesome, and this is the perfect song for the theme!

I walked them through the brainstorming process and gave a preview of what my argument would be. Essentially, I showed them how to integrate songs with rhetorical analysis.

This definitely helped them see what their own brainstorms and arguments could look like.

The Day of the Battle: Battle Structure

On the day of the battle, the students sat in groups of four. They gathered their materials: the song if they were playing a clip, their argument outline, and a writing utensil to take notes on each others’ arguments.

As a class, we reviewed the expectations and structure.

Round 1:

In your small groups, each person takes a turn presenting their argument. Each speaker has 3-4 minutes. After each speaker presents, take 1-2 minutes to reflect on their argument and consider their rhetorical strategies. When everyone has presented, your group votes on the best argument based on your analysis of their rhetoric. In total, these small group rounds would take no more than 24 minutes.

Round 2:

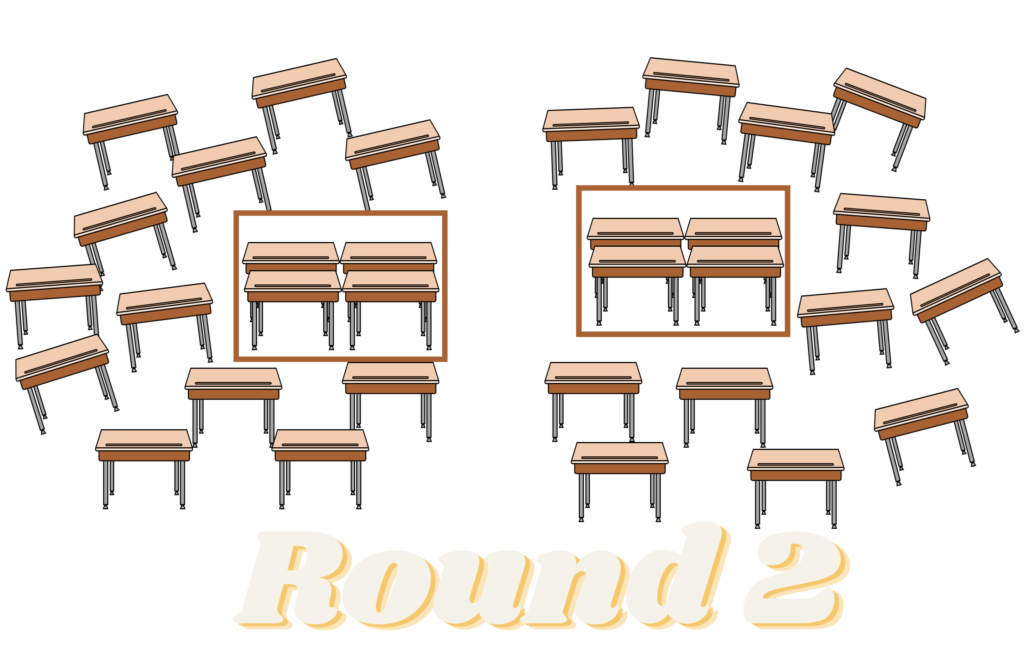

In the semi-final rounds, the rhetorical wizards (students who were voted on) moved seats. In total, there were 8 students who were moving on. The students who did not advance became audience members. This round was a bit tricky to organize physically with the desks. We tried to set up two groupings of speakers, and therefore two groupings of audience members. In these two groups, the semi-finalists presented their arguments in 3-4 minutes, all students kept track of the rhetorical strategies used and quality of the speakers’ arguments. Then, students voted on the best arguments.

Round 3:

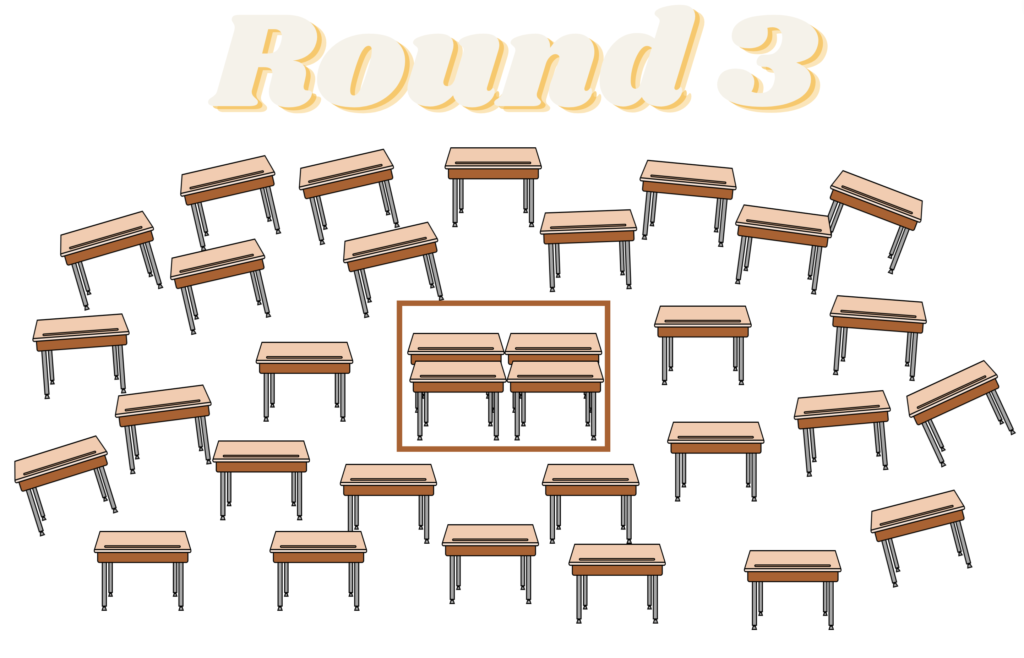

The final round. We moved the finalists to the center of the room–there were four finalists. Just like before, we repeated the same procedures: they presented their arguments within the time limit while the other students listened and took notes on their arguments. We then voted all together for the victor.

After the whole process, I asked students to reflect on the songs with rhetorical analysis; on the process and how this battle went: did they like it? Did they want to do it again? What would make it better?

They had some thoughts!

- We mostly liked it.

- Yes, let’s do it again!

- To make it better we should:

- Find a better way to listen to the songs–it was hard to hear with everyone playing their songs at the same time.

- Not take notes–it was difficult to listen and take notes at the same time, so it felt like they were missing the argument or not really listening.

- Move the seats around better for the semi-final and final rounds–it was too hard to hear this time around.

- Make this more like a debate–people should be able to respond or ask questions or challenge the person’s argument.

I was delighted by their suggestions. They were right, and their willingness to share how to make it better showed their investment.

Next time

As of now, we are in the brainstorming and argument-outlining process for Battle #2. We reviewed our learnings from last time, and I told them how I plan to change the structure based on their advice.

I revamped the note taking doc to be less detailed, but it still has some directives for reflecting on the main claim and rhetorical strategies–but they could take time after the speaker presents to consider these aspects.

We will move the desks better for the second and third round.

There will be time built in to challenge or question the speaker after their 3-4 minutes. Interrupting is rude and stressful–we don’t need that in a civil debate or discussion.

They were excited by these changes; I was honoring their voices and choices. When I released them to begin working on their arguments, the room began buzzing.

One change I did not tell them, winners will be presented with a trophy to the theme song from Rocky.

I found these gems in the kids’ party favor section from Target. They are perfect for this occasion!

I hope you feel encouraged to try your own brave project! If you’re interested in the materials from this Song Battle Project, please visit my TPT store.

Happy teaching! 🙂

Crafting Effective Lesson Plans

Crafting Effective Lesson Plans Teaching The Odyssey

Teaching The Odyssey The Social Dilemma: Social Media Lesson Plans

The Social Dilemma: Social Media Lesson Plans