This post may contain affiliate links, which means I’ll receive a commission if you purchase through my link, at no extra cost to you. Please read full disclosure here.

What is backward design and how can we implement it effectively and sustainably into our teaching practice? In this post, I’ll review the fundamentals of backward design, and I’ll tell you how to use this curriculum design framework.

Do you remember this book?

I do, vividly. It is both creepy and fascinating. Whenever thinking about backward design, I envision the image at the end of the book. The old lady filled up with all of the different creatures she swallowed. As nonsensical as it seems, this image–definitely not the storyline–represents the concept of backward design.

Perhaps a better comparison would be matryoshka dolls. Mmm… yes, visualize that. Much more pleasant! 🙂

So, what is backward design?

Sometimes referred to as backward mapping or backward planning, backward design is a framework for curriculum design. Essentially, it means you plan the curriculum with the end goals in mind. Or, to continue the earlier comparison, you start with the outermost matryoshka doll.

“To begin with the end in mind means to start with a clear understanding of your destination. It means to know where you are going so that you better understand where you are now so that the steps you take are always in the right directions.”

Stephen R. Covey, The Seven Habits of Highly Effective People

As Stephen Covey (1990) indicates, effective people utilize backward design in their own lives. They consider where they want to end up, and then they plan backwards from there. The same principle and logic applies when designing curriculum.

Rather than spending endless time each day setting up activity after activity, feeling like you can never get ahead, you can spend time before the school year begins to consider the ultimate destination for student learning. This time spent considering the end of year goals helps clarify your focus for each unit, and, in turn, each lesson and activity.

In Understanding by Design, Wiggins and McTighe (2005) explain the fundamentals of backward design. As Bowen (2017) puts it, backward design “innately encourages intentionality during the design process.” Another way to look at this, every choice we make in a lesson or in the classroom matters, and each choice should help students learn. Our choices must be intentional. Our choices need to focus on students’ learning, as opposed to focusing on our teaching.

Our choices need to focus on students’ learning, as opposed to focusing on our teaching.

Ryan Bowen (2017) from Vanderbilt University explains, “The backward design framework suggests that instructors should consider these overarching learning goals and how students will be assessed prior to consideration of how to teach the content.”

With the basic understanding of this approach, the question is then, how do you effectively and sustainably implement it?

How do we utilize backward design?

As teachers know, we can spend every waking minute working on lesson plans, and sometimes they still don’t work. While these lesson duds occur for a variety of reasons, sometimes, and in my experience most often, they occur when I haven’t backward planned my lessons. I lost focus. The true goals, the essentials, fell aside.

Maybe I woke up at 2am with a genius idea I wanted to try, or maybe I found a fun activity on Pinterest–I’m not saying anything is wrong with this–but, if I focused more on the activity than on the goals for student learning, then it won’t work out well. Or, if somehow it does, it might not truly benefit my students.

I’m all for fun and trying new things, but we also have a responsibility to ensure we honor the time and effort of our students. We can plan enjoyable lessons and remain aligned with our end goals. And, we can do this without losing sleep (If you’re a new teacher, I’m sorry to say you will still likely lose sleep, but hopefully not because of lesson planning!).

Backwards Design in Practice

Here, I will discuss how to backward design a course. When designing a course using backward design, we start with the course outline, then move to the unit outlines, and finally we create daily lesson plans. While discussing how backward design plays within this flow (course → unit → lesson plans), I will reference two main texts, Wiggins and McTigue (2005) and Fried (2001), to keep the backward design approach grounded in theory.

1. Course Outline

The first step to backward design involves the biggest picture within our realm of control: the course. Before we begin planning individual lessons, we must establish the goals for the end of the course, the end of the school year.

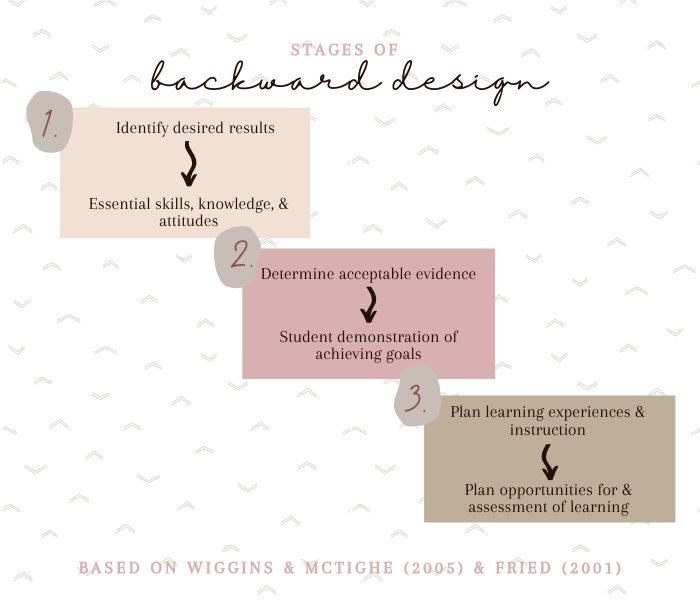

In Wiggins and McTighe’s (2005) book, they review the three stages of backward design.

Stage One.

We start with the biggest picture concept (that we have control over): desired results for the end of the school year.

- What do we want students to know, do, and be at the end of the year?

- What knowledge and skills should participants master? (Bowen, 2017)

- What are big ideas and important understandings participants should retain? (Bowen, 2017)

Similarly, in his book The Passionate Teacher, Fried (2001) advises teachers begin thinking about the “essentials.” For me, Fried’s (2001) ideas provide further insight into how to go about backward planning.

Like Wiggins and McTighe (2005), teachers first define course content by working backward, which means establishing the Essential Skills, Essential Knowledge, Essential Attitudes…) (Fried, 2001, p. 234-235).

These essentials are, redundantly, the most essential part. We must know the end goal. For example, for ELA, this means students can effectively read, write, speak, and listen. These are broad terms, so I suggest working with your department or grade level team to identify the essential skills for students by the end of the entire course–the standards tend to describe the skills, so look for patterns and consider the standards you find most important for your students.

The same process can take place with essential knowledge. What should students know by the end of your course? Remember, students likely remember specific content. My students will not remember that Penelope represents the archetype of the loyal wife, they may not even remember the major plot of The Odyssey. Rather than content comprehension, Fried (2001) explains that essential knowledge “comprises the core content of the course, the things you want students to remember when they’ve forgotten most of the details.”

Essential knowledge, then, can comprise key terms they should know. For my juniors and seniors, this might be specific rhetoric terms, such as logical fallacies. For all my students, key components of essays (thesis, topic sentence, evidence, citation, explanation/analysis/rationale) and the writing process (brainstorm, outline, draft, revise) are essential knowledge.

Essential attitudes, according to Fried, must be clear, consistent, and explicitly taught. Some examples of essential attitudes: “able to take risks in trying to express ideas,” respect for others’ opinions regardless of agreement, or willingness to learn from mistakes.

These essentials should align throughout the course; thus, we must keep these in mind whenever we plan and teach. They are the guide for you and the students.

Stage Two.

The next stage of backward planning framework involves determining acceptable evidence. In other words, how will you know students have achieved the desired results? What can students produce that will indicate they have met those desired outcomes?

This is where you can consider the types of assessments you can use throughout the course, which we will talk about more later in this post. Some assessment examples: essays, open-response questions, and projects.

Like Stage Two from Wiggins and McTighe (2005), Fried (2001) explains that teachers can outline various options for students to demonstrate their achievement of essentials listed above (p. 236).

In other words, throughout the course, what opportunities will students have to show they’ve met these essential goals? There should be multiple and diverse opportunities for students to meet these goals (consider UDL, multiple intelligences, etc.). Essays cannot be the only assessment. Students can demonstrate skills and knowledge in presentations, research and multimedia projects, and they should have opportunities to play to their strengths and to grow. You don’t need to list out every single assignment, but consider the “big” assignments you plan to include in the course, even if to start with these are vague.

For example, in my courses, I generally know I want students to have multiple essay writing opportunities, roughly one full essay per unit; hold various forms of discussions, informal, formal, small group, whole class, digital, face-to-face; read novels they choose for themselves, for fun; read, understand, and analyze different genres of texts; and work with technology to demonstrate their learning. When revising or writing a course outline, these are what I write down and when I move forward to outlining the unit, these will become more concrete.

Stage Three.

In the third stage, you begin to plan learning experiences and instruction. As we are still looking at the bigger picture, we aren’t really planning day-to-day lessons yet. Instead, we are considering what opportunities, experiences, supports, and challenges we must build into the course that will allow students to meet the learning goals.

As Fried (2001) explains, teachers must describe how they will measure achievement level and evaluation (Fried, 2001, p. 236-7). This concept, again, echoes Wiggins and McTighe (2005) stages two and three.

This really means: how will students be assessed throughout the course. Will you use total points or weighted categories? If you use total points, then which types of assignments will have more points? If you use weighted categories, what are the categories and how much are they worth? Typically, at the secondary level, at least in my experience, we use weighted categories. At the undergraduate and graduate level, we use total points. Depending on the program, the syllabus may tell students what each graded assignment is and how much it is worth.

Hook Questions

Fried (2001) also advises establishing themes for the course by asking several “Hook Questions” (p. 235). For me, these hook questions provide further clarity and direction for the entire course. The greatest part about these hook questions? They can be used in the instruction itself! We can pull these question in for a warm up or exit ticket, we can use the same questions throughout the entire course in various ways.

This area of course outlining is deceptively easy. We can just write questions! Well, as we know, writing meaningful and purposeful questions is a challenge. Further, these questions should work well enough they can “hook” students into a subject in which they have little interest. Not only should these questions intrigue, but they should also be approachable.

These questions should not rely on content knowledge students will need to learn in the course. These are “hook” questions, not comprehension questions. These are conversation starters, interest-piquing questions that students can feel comfortable answering without content knowledge.

Fried (2001) states these features for hook questions:

- No “one right answer”

- Lie at the heart of the subject or unit

- Phrased in simple, direct student-friendly language

- Deal with relevant and accessible issues

- Offer choice in how to respond

- Encourage investigation

- Involve thinking and speculating (not just answering)

- Provide a sense of fun an adventure

He also provides some example questions in his book. Here are just a few:

- Are humans the masters of the earth, or only one species on our planet?

- How do people feel when their country loses respect in the world?

- What would it take to make life perfect in our society?

Develop great hook questions and you’ll save yourself loads of time trying to give your lessons and activities focus. Tie any activity or lesson or unit to these questions and you are on your way to aligned curriculum and purposeful learning!

2. Unit Outline

After we outline the big picture essentials of the course, we zoom in on that picture, to a particular focal point: a unit.

The process of outlining a unit echoes that of outlining a course, except, quite obviously, on a smaller scale. Thus, we must keep the above advice in mind when designing the unit; keeping the course goals in mind, after all, is the core of backward design.

Although a unit may last a few weeks or days, we still need to know the end goals, essential knowledge and skills students should grasp by the end of the unit. In other words, by the end of each unit, what do we want students to know, do, and be?

We also need to know the “acceptable evidence.” Similar to the thinking down with the course design, what will show that students know, understand, and master the desired goals?

Lastly, following the Understanding by Design backward design framework, what learning experiences do we need to provide students with so they can produce this evidence and reach these goals?

As Fried (2001) suggests, we can develop hook questions to intrigue students and start building their excitement for the unit.

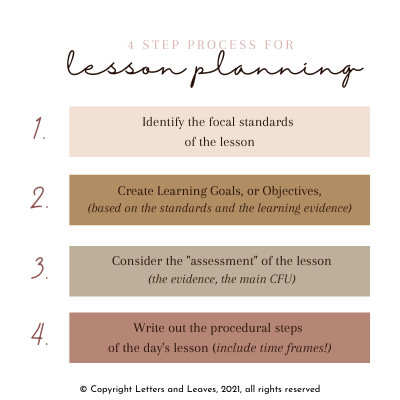

Step 3. Daily lesson plans.

Within a given unit, while considering that focal point of the bigger picture, we zoom in even further: the daily lesson plan.

By the end of this lesson (this day, period), students will…

In a credential program, we learn how to meticulously plan out our lessons. This attention to every detail in a lesson serves a purpose, of course. However, it is unrealistic in the day-to-day world of teaching. This is why unit outlines are so key. If I know the goals of my unit, the standards, the learning objectives (or goals), and content focus, then I don’t need to rewrite these on every single lesson plan. Unless your principal or district asks for formal lesson plans, your lesson plans will likely focus on the procedures.

It is important you know and follow any school or department expectations or guidelines for lesson plans, but, if these are unrealistic, don’t be afraid to ask questions or to offer alternative ideas! In my experiences, I needed a “daily lesson plan” that was visible and accessible to students (on the board or the website); at one school, I also needed a learning objective (“Students will be able to..”), at another, I needed a website with all handouts and resources provided.

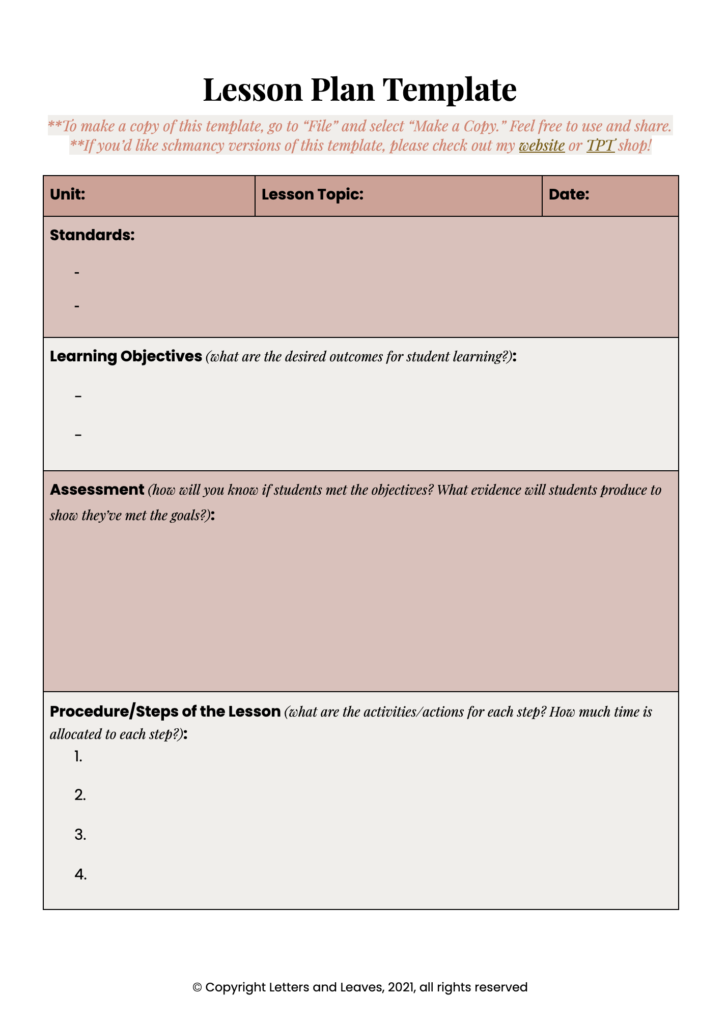

Rather than the overwhelming lesson plans from days in a credential program, we want a simplified, effective, and sustainable plan. For an example lesson plan template, see below. The key to these plans, in regards to backward design: alignment.

Facets of a Daily Lesson Plan

As a new teacher, it is important to know the standards, whether you need to put these on each lesson plan depends on the expectations of your district, school, principal, or department. If you are building learning objectives based on the standards, perhaps you already have them handy or perhaps you don’t need to put them down. In my own experience, I didn’t have a requirement to put them on every lesson plan, and I had extensive training working with the standards in my undergraduate and credential program, so I didn’t put standards on every lesson plan. You do what is best or necessary for you.

Likewise, as a new or veteran teacher, I highly recommend you write out learning objectives or goals for every lesson. (These are the “students will be able to” statements.) If not for your students, then for you, as a check to ensure you are “keeping the end in mind.” And, equally important, to provide purpose for each and every lesson.

I consider the previous two facets of a daily lesson plan as the “business” of the lesson. They aren’t particularly fun, but they are important. The next facet, the assessment, is more exciting. Just like designing the course and unit, we must intentionally determine what evidence students will produce to show they’ve met the goal for the day.

Do you need a formal assessment? Such as a test, quiz, essay, graphic organized or other final product. Or, would an informal assessment work well? Such as a quick write, ticket out the door, or discussion. Determining the assessment necessary depends on the goals and where you are in the unit. Have you covered enough to give a formal assessment?

The final facet of a daily lesson plan where the strategizing comes into play. What are the procedural steps of the lesson? What will the teacher do and what will the students do? Run through the lesson mentally as you plan out the “steps” of the lesson.

Will you start with an opener or an entry ticket? What is the main activity? How will you end the lesson? How will you transition between each step?

This process is what we typically think of when we consider curriculum and planning. But, remember, these plans and procedures take place within a bigger picture, so make sure your steps have purpose!

So what?

As this post indicates, this is quite a lot of work. Why should you do this? Is it worth the time investment?

YES.

Backward design requires significant think time before you teach, before you even sketch out a lesson or activity. However, it will save you time and energy throughout the year.

Ultimately, whether a new or seasoned teacher, the power of intentional backward design is exponential. While some of the essentials for a course or unit or even lesson plan remain the same each year, it is important to consider your students. Who are they this year? What are their specific needs, interests, and strengths? How can you refine your plans, starting with the biggest picture, to best suit the students who entrust you with their present and futures?

When you are planning a lesson, designing an activity, or revising a unit, consider:

What would we do differently if we were to “begin with the end in mind”?

Freebie!

Did you already access the FREE lesson plan template? If not, download it from my shop or Teachers Pay Teachers store!

Want something a little more aesthetically pleasing? Check out other lesson plan templates on my shop or on my Teachers Pay Teachers store!

References

Bowen, R. S., (2017). Understanding by design. Vanderbilt University Center for Teaching. Retrieved January 2, 2020 from https://cft.vanderbilt.edu/understanding-by-design/.

Covey, S. R. (1990). The 7 habits of highly effective people: Powerful lessons in personal change. Free Press.

Fried, R. (2001). The passionate teacher: A practical guide. Beacon Press.

Wiggins, G, & McTighe, J. (2005). Understanding by design. ASCD.

Crafting Effective Lesson Plans

Crafting Effective Lesson Plans 5 Engaging Lesson Plans: Convergence of Self and Place in Jamaica Kincaid’s “Girl”

5 Engaging Lesson Plans: Convergence of Self and Place in Jamaica Kincaid’s “Girl” Song Battle Project: Teaching Songs with Rhetorical Analysis

Song Battle Project: Teaching Songs with Rhetorical Analysis